Relationships and Found Family: Dr. Amy Delaney’s Journey

It’s 11 in the morning and I find myself in Dr. Amy Delaney’s office for the second time in as many weeks. We’re still trying to get to know each other, so I bring in a question that I assume will bring about a lighthearted conversation.

“Let’s talk about your childhood.”

Almost immediately, her smile falls and the air seems to get a little bit thicker. She explains that her childhood was not one she remembers fondly.

“A lot of how I think about my childhood is…very much filtered through that lens of the abuse and the very toxic environment that I had,” Dr. Delaney said.

Dr. Delaney’s childhood was difficult. Due to the situation at home, she had to become comfortable and confident in herself and her abilities earlier than her many of her peers.

Looking at her now and the life that she has made for herself and her chosen family, one would never know of the troubles she had to overcome to get where she is today.

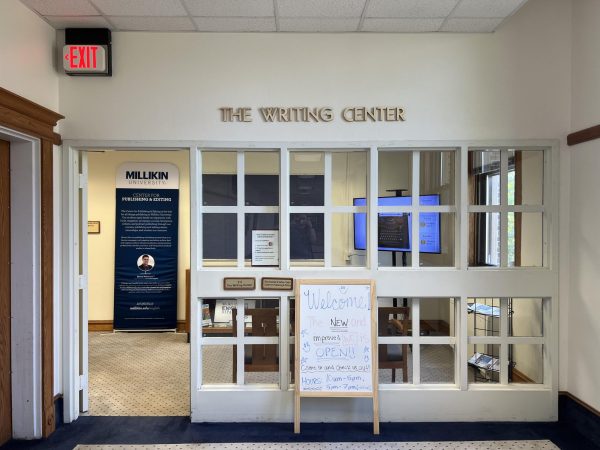

Now, Dr. Delaney is a well-loved professor in the Communications Department at Millikin and successful researcher in her field. She has been able to grow and learn from her past and become happy in who she is and what she has done.

Dr. Delaney is currently doing a study in which she and a few of her colleagues are applying the theory of resilience and relational load. Her study aims to find the answer to the question, “Why do people thrive in response to stress in a relationship and others fail?”

Tamara Afifi and her colleagues who are behind the theory say that “relational partners and family members must perpetually invest in their relationships by maintaining them to foster resilience.”

That is to say, in Dr. Delaney’s words, each person in a relationship has a reservoir of “fuzzy feelings.”

This reservoir is filled by the people they maintain relationships with when they perform duties that invest in their relationships. If someone’s reservoir is filled successfully, they can use those “fuzzy feelings” to help them be resilient in times of stress.

Dr. Delaney’s relationship with her parents did not fill up her “fuzzy feelings” reservoir. She grew up in Washington, Illinois, a medium-sized town boasting just barely over 10,000 people. Her family was a prominent one; her parents were well-known throughout the community and they were generally well-off.

“When she was a child she had everything given to her…as long as she performed the way her [biological] mother wanted her to,” Julie Davison, a friend of Amy’s biological mother and eventual adoptive mother, said.

On the outside, Dr. Delaney’s family was picture perfect. Her biological mother was a CPA turned stay-at-home mom of three children. She was heavily involved in her church and her younger children’s swim team as well as her children’s schooling. Her husband was in upper management in an implement company.

“Staying at home gave her more time to think about how she didn’t like me,” Dr. Delaney said.

Her biological mother’s dislike for her oldest daughter grew as Dr. Delaney began to grow into herself and become more independent from her parents.

The first sign that something was wrong that Dr. Delaney can remember came when she was in the third grade. She had done a worksheet for class and had written something about her biological mother. Dr. Delaney doesn’t quite remember exactly what it said but she knows it didn’t say anything incriminating.

Despite this, as soon as she saw the worksheet, Dr. Delaney’s biological mother flew into a rage. She yelled, worrying about what the other mothers in her community would say if they saw what Dr. Delaney had written. Then she stormed out of the house. In the end, her biological mother was more worried about what others would think of her than what her daughter said.

“That’s one of the main memories I have of thinking, ‘That doesn’t seem right, I don’t think a mother should act that way,’” Dr. Delaney said.

Middle school brought about a new world of independence and autonomy.

Essentially, Dr. Delaney was blossoming into herself and beginning to learn who she was as a person. Unfortunately, who she was becoming was not someone that her biological mother really liked.

“She had a very specific idea of what kind of daughter she wanted, and when I wasn’t that person, she just seemed pretty incapable of loving me,” Dr. Delaney said.

Despite her home life, Dr. Delaney was able to find comfort in her job throughout high school. She worked at a restaurant called Katie’s Cafe that was run by a man named Jerry Hamilton. The restaurant was named after his daughter, Katie.

Katie’s Cafe was a refuge for Dr. Delaney when she needed to be away from her biological mother and her abusive tendencies. She would open in the mornings before school and make sure that the restaurant was prepared for the rest of the day.

Katie’s Cafe was a place that made Dr. Delaney feel valued and appreciated.

“When you have a mom who treats you like you’re garbage and acts like you’re not worth anything, it felt really good to have a place where you felt valued and appreciated,” Dr. Delaney said.

Jerry treated her with kindness and respect and always made her feel welcome. She loved the customers and interacted with them frequently.

Amy had people in her corner, quietly trying to help from the sidelines as the situation with her biological mother became more and more intense. Two of those people were Julie and Dale Davison.

Julie was an aerobics teacher at “The Gym Corner,” which was the gym that Dr. Delaney did gymnastics at. Julie took a step aerobics class with Dr. Delaney’s mom, and after class, she would have conversations with her. These conversations sometimes involved Dr. Delaney. Her mom would confide in Julie about how upset she was with who Dr. Delaney was becoming and how “difficult” she was being.

“Her mom confided in me,” Julie said. “I knew it was really dire towards the end.”

And the “end” was indeed near. It all came to a head during Dr. Delaney’s junior year.

Around that time, it was decided that she would stay with someone for a week or so. The people she was supposed to stay with canceled, so Julie and Dale volunteered to house her for a bit. A week went by and things were still rough at home, so Julie and Dale sat Dr. Delaney down and offered a solution to her problem: stay.

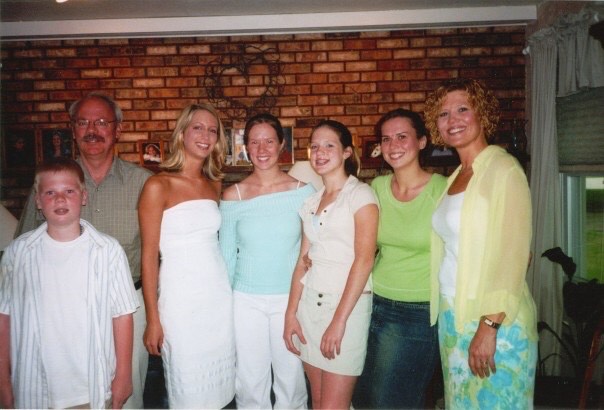

For the next year and a half, Dr. Delaney stayed with Julie and Dale and began to integrate herself into the already large family. With four kids, two home from college at times, plus Dr. Delaney and Julie and Dale, the modest house became a little crowded. But that was worth it because Dr. Delaney finally lived in an environment in which she was loved and supported.

She gained four new siblings for the ones that she had lost (they were young and sided with her biological mother in the situation), and she was more than welcome to become part of the family.

Dr. Delaney has been with her adoptive family ever since.

“I have spent more of my life with my family than I did with that [her biological] family,” Dr. Delaney said.

She has made a new life for herself in which she has learned what it’s like to be truly loved, valued and cared for. She has also learned how to successfully love, value, and care for the people that have supported her and helped her be happy.

Growing up, Dr. Delaney’s emotional reserves weren’t being filled by her parents. But, she was able to fill it when it came to other relationships. Her relationship with who she now considers her parents, Julie and Dale, was maintained through communication and their working to integrate Dr. Delaney into the family.

That relationship grew throughout her college career through phone calls and trips back home during breaks. She called Dale every Wednesday night, sometimes on her way home from class, and Julie remembers that Dr. Delaney would call almost every day during her first year.

Making sure that the people in her life know that they are loved is important to Dr. Delaney, especially when it comes to her four-year-old daughter, Nora. Dr. Delaney knows that Nora knows that she loves her, and one of the ways that Nora knows is that Dr. Delaney “does nice things for her.”

Dr. Delaney makes sure to pay attention to what Nora has to say and provides all of her attention when Nora wants it. She puts down her phone when Nora speaks to her. She looks at her and she engages in conversation.

Another way she shows Nora that she is loved is by “cooking” with her. Dr. Delaney will be cooking dinner and Nora will take a large plastic tupperware container and start “making a meal” with her. While Dr. Delaney’s food is certainly edible, Nora’s meal usually includes water, some bread, and a bunch of spices. Sometimes Nora will ask Dr. Delaney to try her food, and Dr. Delaney will take the smallest of bites.

Dr. Delaney also explicitly tells Nora that she loves her and listens to her even if she disagrees. By looking back on what her own biological mother had done, and through outside research, Dr. Delaney has been able to parent Nora in a way that is much better than her biological mother’s parenting.

She makes sure that he daughter loves life and even shares her love for gymnastics with her. She takes Nora on trips so she can explore (Nora’s favorite place on the planet is The Great Wolf Lodge, and she will sometimes pack to go without being prompted).

Now, a big part of what Dr. Delaney does with her daughter has to do with respect.

“Part of love has to be respect,” Dr. Delaney said.

She respects Nora’s autonomy, something that Dr. Delaney’s biological mother had not done, which caused some of the abuse that Dr. Delaney had experienced.

Because of her own experiences with her biological mother, Dr. Delaney didn’t always want kids. She was afraid that she would hurt someone in the same way that she was hurt. But she realized that if she and her husband, Tim, did it together, then she could successfully raise a child.

The relationship between her and Tim is one in which Dr. Delaney deposits into the “fuzzy feelings” reservoir often. She does this by communicating with him daily, often through text messages throughout the day asking how his day has been and planning for their evening and general small talk. They listen to and learn from each other.

They are also focused on working together as a team, not only in parenting but also in their lives together. Working as a team was even mentioned in their wedding vows.

They take turns picking Nora up from places; they see each other as partners in their parenting. Before they had Nora, they hosted get-togethers with their friends, and they would both plan together and prepare for them as well as clean up after them. Dr. Delaney understands that it’s important to see each other as equals, and she works to make sure that she and her husband continue to work together as a unit rather than separately.

While no student has approached Dr. Delaney for help about their own familial issues, she has used her past experiences to help students who may be facing their own familial situations.

“I’ve…given a bit more depth and detail to students who might be in their own challenging family situations,” Dr. Delaney said.

She doesn’t usually explain her own past trauma and experiences in detail unless she feels that it would be beneficial for the student.

“When I suspect a student would benefit from therapy, I might disclose that I’ve spent my own time in therapy/counseling to process my family life, and with that I might give some information about what happened,” Dr. Delaney said.

Due to her complicated history, Dr. Delaney treats students a little differently than how she might have if her parents had contributed to their relationship in a positive way.

“I always try to think of my students as whole people and to respect their autonomy,” she said, which is not so different from the way she parents Nora. She works and communicates with her students, and she practices empathy when interacting with them.

“Honestly, I think the foundation of good relationships with my students is the fact that I genuinely like them as people…. I enjoy getting to know them. With that as a starting point, we can maintain productive educational relationships as we work toward the shared goal of enhancing their knowledge and skills,” Dr. Delaney said.

By being genuinely interested in them as people and asking them questions and checking on their overall wellbeing, Dr. Delaney contributes to her students’ emotional reserves.

What we can learn from Dr. Delaney and her experiences is that, in our relationships, we need to all work to make sure that we’re contributing to them in ways that fill the other person’s “fuzzy feelings” box.

If one person isn’t giving something to a relationship, or what they are giving is overwhelmingly negative, the relationship will fall apart.

Dr. Delaney’s biological mother contributed negatively to their relationship and was emotionally abusive. Their relationship fell apart, and Dr. Delaney hasn’t talked to her biological mother in years. She will never talk to her biological mother again, for she died a few years ago.

We must think critically about how we treat others and how we communicate with others. “As people, we have some degree of control over what happens in our lives and part of what we can control is how we communicate with others…We can do better and we can be strategic in how we navigate our relationship.”